How Listening for Details Will Transform Your Playing

When we start out learning jazz, we’re often told by our teachers and elders which recordings are important to check out. This is incredibly helpful, because it saves us from navigating the sea alone, shining a light on the works that have historical significance – the stuff you really should know because it helped shape the language of the art form. These recommendations continue on from there: from teachers and elders, yes, and increasingly from mentors, artists we admire, friends we play with, colleagues, cats we know who are into the same stuff as us, cats we know who are checking out some different stuff.

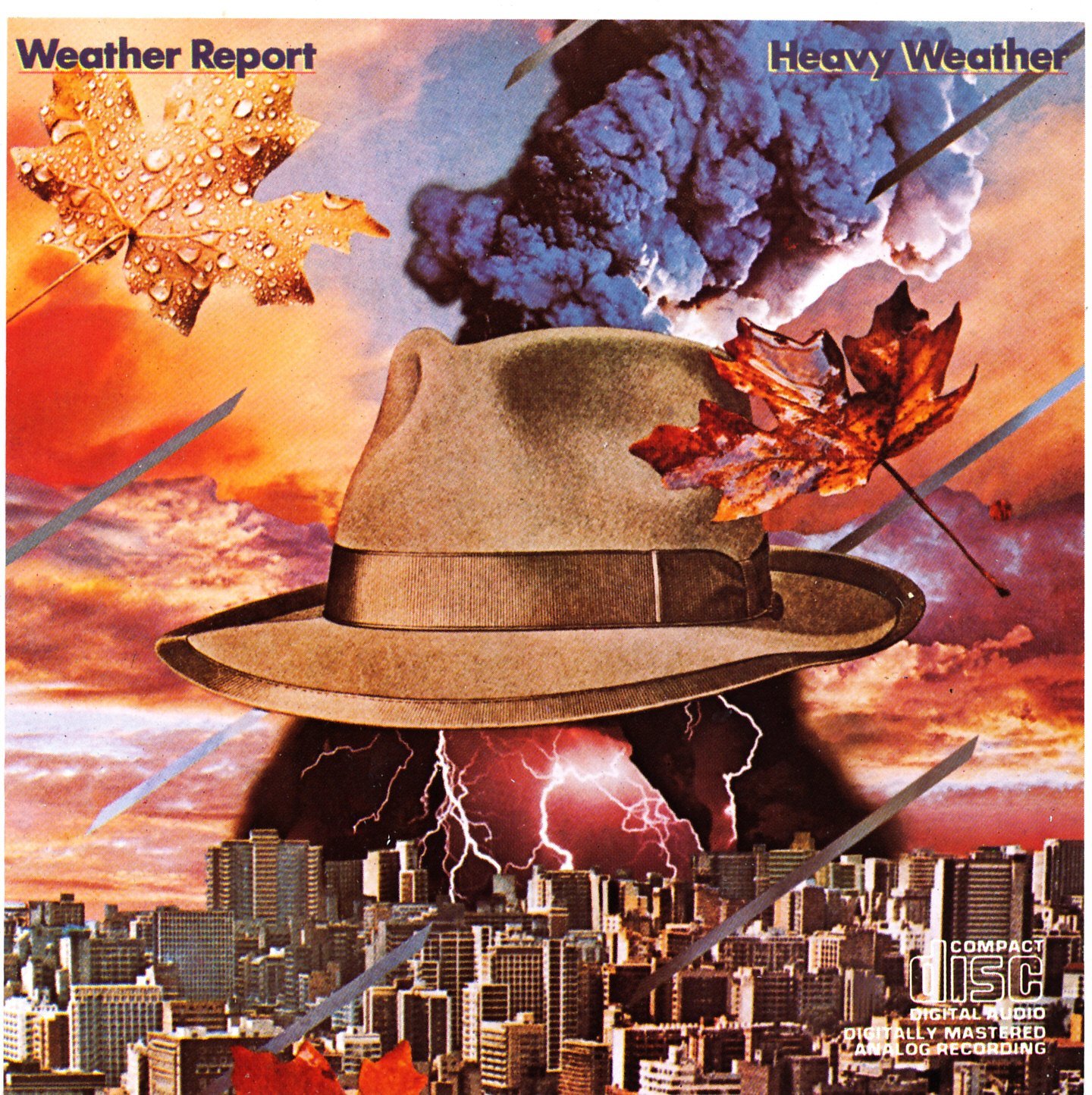

The recordings and artists are always clearly stated: The Hot Fives and Sevens, Bird with Strings, Kind of Blue, Heavy Weather, That Disc from The Artist who just played Your Local Club. Nothing to figure out there; it’s all clear. But when talking about why those recordings are important, the language turns more abstract. Words like “swinging,” “burning,” “happening,” “amazing,” “iconic,” “beautiful.” Phrases like, “makes you wanna dance,” “made me wanna cry,” “incredible flow,” “still sounds modern today.” The feelings you may identify with – maybe you even know a bit about what kind of “burning” they’re talking about. But what is happening in the music to make it that way? Quite literally, what is happening in a particular recording that makes it sound so swinging? What is the band doing that makes you want to dance?

What is “Listening for Details” (and Why Does it Matter)?

Listening for details means focusing in on a specific aspect of a track and processing as much detail as you can about that aspect over a series of listens. Repeat as necessary. That’s it.

It’s important to point out that this does not mean listening intently for all the details. Oh no. We’ve got to break it down. If we’re listening in service of building our craft and/or our artistry, we’ve got to be intentional about the process – and indeed it is a process – and the more organized we can be, the easier it is to know what we’re working on, why we’re working on it, and if we’re making progress.

Listening for details means focusing on a specific aspect of the music when listening: the beat placement of a particular player’s lines, the inflection of one part of a phrase, the pattern (or beat placement) on the ride cymbal. By narrowing the focus of what you’re listening for, you can adopt an investigative role in your listening and absorb more detail in the process.

And as you focus on that specific aspect, you want to process as much detail as you can each time you listen. When you do, you discover more as you investigate: details become clearer, questions arise that make you want to go back and listen again to find the answer, new discoveries may lead to new questions and new searches. Bit by bit, over time, this process leads to you having cultivated an understanding of what you’re listening to, and through that, the ability to recognize and parse what is at the core of all artistry: making choices. By recognizing the choices that artists make, how they’re doing it, and the intended or resulting effect, you have both a developing lexicon of the choices that can inform artistry and a framework of understanding from which you can base your own choices.

Whether that lexicon and your own choice making is already at hand for you or far down the road, the process has immediate rewards right from the start. I mean, isn’t discoving something fun – even if it’s been laying in wait for fifty years?

There’s another huge part of this that needs to be mentioned: when listening for details – when all is going as intended – you are in charge of the whole thing. You started it, you’re following through with it, you’re discovering more, you’re documenting your observations and questions… You’re making this happen. And this isn’t to say that you operate in a vacuum. Oh no. Other people in your world have even greater significance in your life when you’re doing this: teacher and mentors answer emerging questions, peers are sounding boards to your discoveries. By cultivating a greater connection to what your hearing – to the music – you also cultivate a greater connection to your community.

Let’s talk about how to do this, and first, some related terms and shout-outs to research and work that’s been done on this. After all, nothing exists in a vacuum.

Science and the Edu-Sphere

Whether it’s our physical health, our mental well-being, or how we learn, scientists have been very curious about music and it’s relationship to people – and of course the role of musicians is integral to that research.

Johns Hopkins researchers have had dozens of jazz performers and rappers improvise music while lying down inside an fMRI (functional magnetic resonance imaging) machine to watch and see which areas of their brains light up.

“Music is structural, mathematical and architectural. It’s based on relationships between one note and the next. You may not be aware of it, but your brain has to do a lot of computing to make sense of it,” notes one Johns Hopkins otolaryngologist.

In education, an existing term that is closely related to listening for details is active listening. According to an article from the Yale Center for Teaching and Learning, active listening requires “a heightened level of engagement from the observer or listener but also resulting in a greater acquisition of knowledge.” Said more simply in the same article, “active listening is listening with a purpose.”

Granted, with many such articles and endeavors, the effort to be definitive and resource-rich can render its language distant and affected, intellectually linked to the Ivory Tower and lacking in accessibility – as was the case with Yale when they continued to break down three sub-types of listening as Affective, Structural, Dialogic. Interesting for educators, quite likely. Interesting to non-pedagogues, likely not.

I’ll note that the term “listening for specific information” also exists in education. This term is used to refer to a type of critical listening skill, and generally refers to the ability to “involve analysis of the information being received and alignment with what we already know or believe.” While this statement has some overlap with listening for details, “’specific information’ refers to exact, precise fact or description of something mentioned,” and is therefore objective. Since how we hear music and the expression of music is inherently subjective in nature, listening for specific information isn’t an accurate fit.

“Listening for details” is intended to be plainspoken language, because everybody can do this, and everybody can discover new things when listening in this way.

That feeling when you hear something you didn’t notice before.

How to Listen for Details

Listening for details is much like looking up close to a painting, for example. You might suddenly see the texture of the painting, the brushstrokes, new colors that you hadn’t noticed were there, and when you step back again and look at the whole picture, you see it in a new way. Except that we can’t literally lean closer to the music. When we pause a track, it ceases to exist. That said, there are a couple of things we can do to help set us up for listening for details: we can narrow our focus, choosing one aspect of the music to pay attention to, and we can also form a question to guide our investigation. We choose our area of focus before we listen for details, and keep our focus there while the music plays (this can also mean not focusing on other elements of the track at times, like disregarding the soloist if you want to focus on an aspect of the comping, for example). And much as you need the lights to stay on so that you can keep looking at a painting, you keep repeating the track as necessary so that you can keep listening to the music.

An important note: before choosing an aspect to focus on for details, be sure that you’ve taken in the whole track first. Having at least a rough impression of the whole track gives you context for what you’re exploring – you want to soak in the vibe of the piece before investigating what went into making that vibe. Plus, if you’re not coming at the track with some questions already at the ready, listening to the whole track will help you come up with some.

Once you have an impression of the whole track, narrowing your focus will enable your discovery. What are you listening for, and can you be more specific about that? Here are some examples of getting more specific:

Are you checking out the time? What aspect of the time? The feel (swing/straight)? Beat placement (on-top/laid-back)?

Are you listening for a group of musicians (how they interact) or one individual (how that person plays)?

Are you listening for details through the whole track or a portion of it?

You may also want to keep in mind:

Listening to one musician at a time can be helpful, depending on what you’re focusing on. For example, if you’re curious how two or three musicians are interacting with each other, it can be really helpful to focus on one of them at a time, noticing the details of the individuals, and then look at your notes and shift your attention to listening them collectively.

Be specific about what aspect you’re listening for when listening to an individual in a group. You could be listening for the time feel or beat placement of the soloists quarter notes in a phrase, for example. You could also be listening for the feel or the placement of the comping, of the bassist; of the drummer (which means listening to the different parts of the kit).

Then listen – and take notes. Then listen again – and take more notes. Seriously, notes really help you keep track of all the details you’re hearing – and those notes are really handy once you’ve done several listens. Questions inevetably come up during listening, and you’ll want to write those down, too. Common questions that come up can be about something you just heard (“Did they just…?), how something was done, or about something more subtle (“Why/How did they…?”).

When you’ve gotten some details and questions down, exercise the option to go big, small or in between: listen to the whole song, large excerpt, or small excerpt.

Let’s try this out with the example of All Blues, the Miles Davis tune from Kind of Blue. Listening to just the introduction, let’s start with the question, “What’s the mood of the intro? How would you describe it in one or a few words?”

So, how would you describe the mood? Maybe you’ve described the mood as “chill,” or “cool,” or “smooth,” or “rainy day” or something else entirely. The point of this is for you to describe the mood as you’re hearing it.

The next step in getting to details is the what/why/how/whom. In this case, once you have a description of the mood, the next question is, “What are you hearing that makes you say that it’s (chill/cool/etc)?” Then listen with that question in mind and jot down the details you’re hearing. If that leads to another question with more detail, then continue digging deeper. And if not, listen for details that could answer that question.

Give it a try for yourself, and remember to listen again as necessary until you are satisfied with the information you’re getting:

Listen once with the question, “What’s the mood created here?”

Once you have a mood, listen with the question, “What am I hearing that makes me me say the mood is that way?”

At this point, you may be hearing more details yourself that lead you to investigate in a certain direction. Do that.

Or, you could go deeper with each musician, listening for what they are doing that helps to create what you’re hearing. For example, “What am I hearing the drummer play that sounds [how you described the mood]?”

The repeat the process with each musician: “What do I hear the pianist (or bassist, or horns) play that sounds [mood]?”

Then pull your focus out and listen to the whole band. How are you hearing things now?

New details can become clearer to you now, and additional questions can arise. You may be just listening to the intro here, but it can easily happen that you go deep into a short section of the music.

So that’s an example of listening for details with the intro. Form here, you could listen to the rest of the head with the question, “Is this mood continued once Miles comes in with the melody?” Depending on the answer to that, you can investigate further – and I imagine you are starting to see how that plays out.

What to Do with What You’ve Heard, and How it Will Help You

There are so, so many ways that this process can help ¬a musician – many more than I could write here ¬– but here are several ways you can use what you get from this process, separated in to the time frames of immediate, near term, and long term.

Immediate

Answers

You know all those questions that came up? Sometimes, they can’t be answered by listening again (“Why is the turnaround in All Blues different than other blues that I know?” for example). In that case, take these questions to your teacher, a mentor, or an elder who knows their stuff (peers can help, too, especially when you are more advanced). Teachers, mentors, and elders typically enjoy these questions, because they come from your curiosity, from your sincere interest in the music, and your questions show that interest. Also, because you came up with the questions, the answers you hear will matter more to you (you’ll remember them longer, too), and more often than not, you’ll end up learning more than you set out for when you asked the questions in the first place.

Listening

Go back to and listen to the whole track, without any intended focus, and see if you find yourself processing more of what’s going on, as it’s coming at you. You’ll experience a sense of growing familiarity; an understanding of the material cultivated by you.

It’s much like getting to know your friends: you grow to understand them through many shared experiences over time. Much like you grow to understand the idiosyncracies of your friends, you grow to understand the “isms” of certain players and of the unique traits of certain combinations of players.

Playing

Go to your instrument and emulate what you’ve just listened to ¬– same tune, same key, etc. You may not do it exactly as you heard it, especially right away, but you’re more connected to the music, you know more intrinsically how it’s supposed to be, and the path to getting there will be clearer.

Near Term

Recognizing the details you’ve heard as being choices, you’ll hear more details ¬– more choices ¬– more readily. You’ll also recognize the choices you make when you play. Or, if you’re not yet at a level that you make choices, you’ll start seeing opportunities where they can happen, and most importantly, you can better identify what you need to work on to develop the skills/material necessary to make them.

Long Term

When you recognize the choices that go into making music, that informs you as an artist yourself, and equips you to be intentional with the choices you make.

Reminders for Listening for Details

Narrow your focus

Choose a question to guide you

Listen (again and again)

Take notes

Zoom in; zoom out (as necessary)

Remember, this is about process, not product, and there is no “right” answer.

Make it Come Alive

In addition to the questions that come up, take your findings to your teacher, a mentor, and/or to a friend who shares your interest. It’s fun to share what you hear, to hear their response and feedback, and hear from them as well. We never just learn from one direction or experience; this is a way to deepen your understanding and build on your initial effort.

You Can Always Listen More Deeply

The language of jazz is spoken by the masters on recordings, and there is a wealth of information in every single recording you listen to. What you discover depends much on where you’re at when you’re listening – both your ability and where you put your attention – but there are things you can do to set yourself up for discovery, and make sure you get as much out of it as possible.

Whether you’re in the nascient beginnings of learning jazz or a seasoned pro, you can always listen more deeply for details in the recordings you’re listening to. Develop this skill and you will be surprised at how much you discover.

Like what you’ve read here and want more insights like this? Sign up for our newsletter!